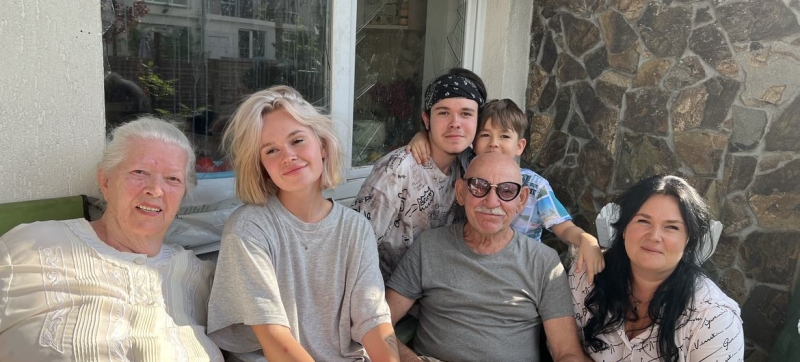

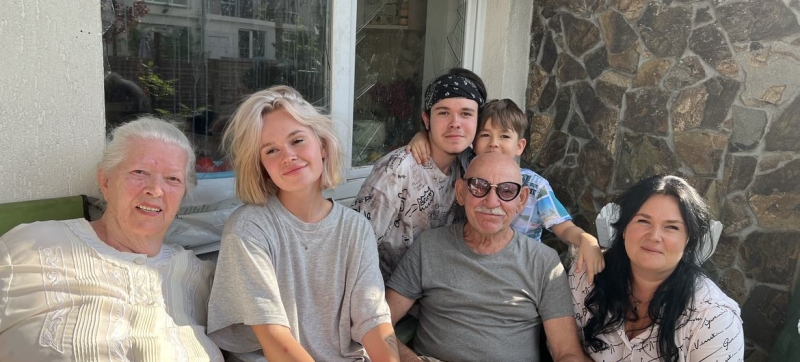

Lyubov Baziv with his family in Gostomel in the summer of 2022. Former refugee: “We never planned to leave Ukraine forever” Refugees and migrants

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), two years after the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, more than a million Ukrainian refugees have returned home from abroad. One of the main reasons for this decision is longing for his native land. This is evidenced by both the organization’s surveys and the stories of Ukrainian families themselves. About one of them – in the material of the UN news service.

The beginning of a full-scale invasion found Lyubov Baziv and her three children not in Ukraine – the family was spending their vacation abroad.

“On the morning of February 24, we were in complete shock. My first desire was to return urgently! But air traffic was already closed. We were eager to go home, because our parents remained in our house in Gostomel, which literally in the first days of the full-scale invasion was already occupied by Russian troops. Contact with them was completely lost. And these are very elderly people who would not be able to evacuate on their own. We tried to contact them again and again without success. They were looking for volunteers who would help take the elderly out of Gostomel. There were even “stalkers” (ed. – people who explore abandoned places) who tried to get into our neighborhood to help them. But everything was unsuccessful. No one could get there, because it was extremely dangerous,” says Lyubov.

“Grandfather and grandmother survived by a miracle”

“Our grandparents were able to survive by some miracle – under constant shelling, in a broken house, with broken doors and windows… What saved us was that the box remained. The neighboring houses were completely burned when a shell landed in the yard. We had a wonderful apartment complex next to a park that had been renovated the day before. It was a garden city. It’s good that the parents are thrifty and managed to collect technical water. They prepared food for themselves over the fire. We managed to pick up my grandparents from Gostomel only at the beginning of April. It’s difficult to convey what two 84-year-old men experienced there,” recalls Lyubov. – My parents moved to the Kyiv region in 2014 from Crimea, after the annexation of the peninsula by Russia. They lived their whole lives in Sevastopol. But at that moment they said – we won’t live here anymore. Among our Gostomel neighbors there were many immigrants from Crimea and Eastern Ukraine. And now these people have lost everything for the second time.”

Lyubov’s parents settled in peaceful Gostomel a month before the start of a full-scale invasion.

“The actors played for people in air-raid shelters”

“We never planned to leave Ukraine completely, so we returned home to work. I am a journalist, writing about culture. But from that moment on, all of us had no time for cultural entertainment. Therefore, I continued to write about actors, but they were doing something else, their type of activity had completely changed – some went to the front, some became volunteers. In a word, the news I had was not about the prime ministers, but about who raised how much for the army, how much humanitarian aid was donated, and what useful things they did for the military. In the very first days of a full-scale war in Irpen, our wonderful actor Pasha Li, who was trying to help people in the occupied city, died.”

Lyubov Baziv at the Ivan Franko National Academic Drama Theater.

“I remember how the actors told me that our profession is no longer needed. What a theater during the war?! But then they realized that people wanted to at least hold on to something. And some started playing for their audiences in bomb shelters, in underground passages, some staged performances in the subway,” says Lyubov. – The Ukrainian theater continues to work now, maintaining the morale of Ukrainians, despite constant air raids and missile attacks. Because our culture must live.”

“Three children returned to Kiev, the daughter dropped out of school in the USA”

“Soon all three of our children returned to Kyiv. They could not accept life away from home. The youngest son was very sad and wanted to return to his school. The eldest daughter especially amazed us. Long before the full-scale invasion, Eva entered a university in the United States (in New York) and had already been studying there for some time. Unexpectedly for us, she decided to take the documents and return to Kyiv. And no matter how much we tried to explain to our daughter that it was better for her not to quit studying in America, no amount of persuasion helped. “I can’t be there when you’re all here!” – she said, snapped, and returned to Ukraine. I have heard many similar stories about how young people are returning. They are brave, they are not afraid, they have youthful maximalism. For them, uncertainty abroad is worse than bombing at home. I even talked about this with psychologists. Of course, the person whose house is bombed is much worse off, and we are not comparing this. But psychotherapists confirm that it is also very difficult psychologically for people who are far from home, and often much worse than we imagine. I know from myself what it is like when you are physically unable to react, to control that, for example, everyone goes to cover during an air raid raid. Physical presence is very important for young people,” shares Lyubov.

“In the fall, the war reminded itself with renewed vigor”

“After several months of conditional calm in Kyiv, the war reminded itself with renewed vigor. On October 17, 2022 (I remember that day exactly) an attack drone flew into our yard. It hit a residential building right in front of our windows,” Lyubov recalls with horror.

Destroyed houses in Gostomel.

“It was creepy. We all – me, my husband and children – were at home at that moment. We live in the city center in a high-rise building, on a very high floor. At that moment, no one was able to go down anywhere; they only managed to lock themselves in the bathroom together, together with the cat and dog. There was a strong impact and a lot of smoke – it seemed to us that it hit our house directly. But when we finally began to go downstairs and went out into the yard, we saw that the neighboring house, standing right next to ours, had been bombed. The floor of that house was simply blown away, people died there, among whom was a young couple (the woman was pregnant). The school nearby where our youngest son goes was also hit (the windows there were broken). Therefore, the children could not study for some time. After this, Russian shelling of the capital became regular. Due to hits on the city’s energy facilities, permanent power outages began. We realized that the children needed to be taken out again, at least from the center to the suburbs. Because for residents of high-rise buildings, the lack of power supply meant a loss of light, heat, water, and, importantly, the elevator stopped working. All this forced us to move to our parents in Gostomel, where by that time we managed to partially restore the house. And it was a real flashback – winter again, Gostomel again, air raids, broken houses around. But at least there was a basement and a generator could be installed. And so they did. We returned home again in the spring, when the situation had more or less stabilized.”

“Despite the shelling, Kyiv lives an active life”

“Russia regularly shells Kyiv today. But, despite everything, the city lives! – says Love. – The educational process has completely resumed at my son’s school. The child goes to 3rd grade with great joy. Almost all of his classmates returned. Our two older children are students. The daughter entered Kyiv to study directing, the son to the Faculty of International Business. They don’t want to leave anywhere in the future. Before the full-scale war, the pandemic made adjustments to the educational process of children. Young people then got used to “living online.” Now this helps, because even with those friends who have not yet returned, the children communicate in chat rooms. They are different from us, our children are different. In general, the ability to do a lot of things online helped us all a lot during the war. Some could continue to work and pay taxes, others could study and not lose touch with friends.”

How to talk to children about war?

“Many people ask me how I talk about the war with my youngest child ? He is eight years old. He knows that there is a full-scale war going on, that Russia attacked us. Of course, we don’t show our little son shocking photos; we give him information appropriate to his age, because the child’s psyche is fragile. But he knows what paradigm he lives in: if there is an alarm, we are taken to a bomb shelter and continue to study there; if there is a threat of a missile attack in the morning, we don’t go to school. Yes, this is his childhood, it goes like this. At first we were worried and doubted, for example, whether to celebrate the child’s birthday, but then we realized that there would be no second childhood, therefore, no frills, but children should have small holidays. They might, for example, get ready and go to the playroom.”

The childhood of Lyubov’s youngest son passes against the backdrop of war.

New habit – helping and “donating”

“Adults also have new habits. Foreigners often ask me about them, expecting to hear about how we now run for cover or endlessly stockpile food. But it’s not quite like that. Our main new habit is to constantly help. Some choose large volunteer or charitable foundations, while others help in a targeted manner. All of us who are not directly at the front live with a sense of guilt, this is called the “survivor complex.” It is easier for those who are engaged in socially important work (teacher or doctor) – they are already making a big contribution to a country at war. The rest donate (donate money) and do something useful for the army. You can say that we, the survivors, are saving ourselves with this,” shares Lyubov.