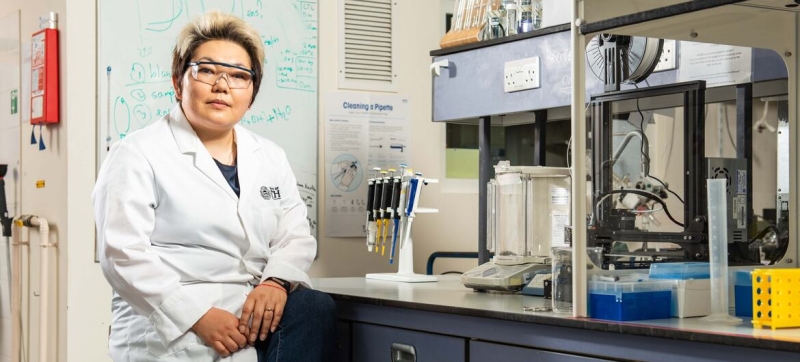

Chemist Asel Sartbaeva in the laboratory. INTERVIEW | Developments by a scientist from Kyrgyzstan could change the global vaccine storage system Evgenia Kleshcheva Women

How a student from a rural school in Kyrgyzstan was able to get into the best universities in England and develop a technology that could change the global system of storage and delivery of vaccines ? On the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, UN News Service spoke with chemist and entrepreneur Asel Sartbaeva – UNICEF Ambassador “Girls in Science,” which helps Kyrgyz schoolgirls believe that research and discoveries can be part of their future.

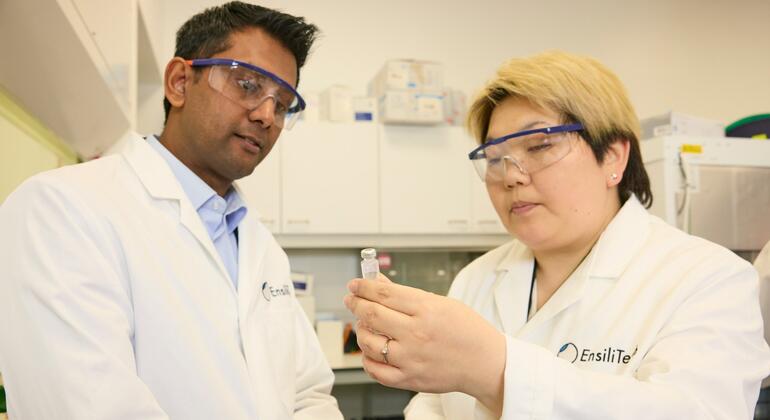

As a child, Sartbaeva studied in a regular rural school in Kyrgyzstan and loved mathematics, physics and chess. Today she is a Cambridge graduate, an associate professor of chemistry at the University of Bath in the UK, and the founder of a technology company. EnsiliTech.

Her research is aimed at solving one of the key global health problems: how to make vaccines resistant to high temperatures so that they can be delivered to the most inaccessible regions without complex refrigerated logistics.

From mechanics to biotechnology

The future scientist’s school years coincided with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Despite the general instability that reigned throughout the region, according to Sartbaeva, she was lucky with strong teachers who helped develop her interest in the exact sciences.

While studying at the university in Bishkek, she twice became the winner of the Republican Olympiad in Strength of Materials – and was the first girl to succeed. This success strengthened the desire to continue a scientific career.

In 2001, Asel received a scholarship and the opportunity to go to the UK to study at graduate school at Cambridge. There she began studying silicon materials, and later zeolites, which are widely used in a variety of areas: from washing powders to the elimination of the consequences of radiation pollution.

The question that changed direction research

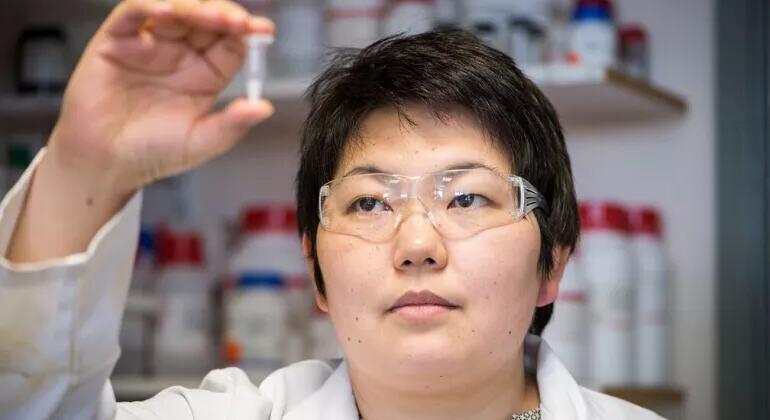

The turning point was the birth of her daughter. The researcher was working in Oxford at the time. At the local clinic, Asel saw the vaccine for her child being taken out of the refrigerator, and asked why it cannot be preheated. The answer that the drug could go bad prompted a new research search.

The scientist wondered if it was possible to use knowledge about silicon to create a protective shell of biomolecules that would prevent the destruction of vaccines when the temperature rises.

It took years to develop and test the idea. The first convincing results were obtained only after almost a decade of laboratory work. Subsequently Sarbaeva called the new technology she developed – “ensilification”.

According to she the problem of transportation remains critical: a significant proportion of drugs is lost, and millions of children, especially in low-income countries, do not receive timely immunization.

“In many places there are no roads, reliable electricity or refrigeration,” she notes. In mountainous countries such as Kyrgyzstan, vaccines are delivered to remote areas on horseback. In island countries – on small boats. Sometimes vaccinations can only be delivered to hard-to-reach communities on foot in portable containers. existing and new drugs. The goal is simple: to make life-saving medicines available to those who need them most.

Science and equal opportunity

In addition to research, Asel is actively involved in educational initiatives in Kyrgyzstan as an ambassador for the UNICEF program aimed at supporting girls in fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

She said that in many families, parents make decisions about their daughter’s future, and therefore it is important to work not only with schoolgirls, but also with their loved ones, especially fathers. In some communities, girls are still discouraged from going to university or choosing technical professions. Financial dependence in the future can increase the risks of poverty and violence.

“I often hear the fear that if a girl becomes a scientist, she will not have a family. It was important for me to show that this is not so. You can be a scientist and have children. These things are not mutually exclusive,” says Assel.

The Girls in Science program includes master classes, meetings with mentors, development of communication skills and self-confidence. All this, Sartbaeva emphasizes, helps girls believe in their own strengths. The initiative turned out to be much larger than originally planned. It allowed us to support thousands of girls and boys who, thanks to the project, gained self-confidence, communication and leadership skills.

The results are noticeable: dozens of graduates chose STEM majors. Many of them admitted that they had never even thought about such a possibility before. If previously there were almost no female role models among teachers, today the gender composition of universities is more balanced. Inclusive measures in education and science benefit everyone, not just girls, the researcher emphasized. However, the need for new specialists remains.

Assel is convinced: education opens the way to independence and expands life opportunities. At the same time, according to her, science needs a variety of talents – experimenters, theorists, programmers, communicators. Dislike for one direction should not become a reason to abandon the entire field.

“This is especially true for girls who plan to study STEM disciplines, chemistry, physics, mathematics, engineering. I would say that we absolutely need you. We need you in all these areas,” Sartbaeva emphasized.