Testing “Licorn” in French Polynesia. INTERVIEW | New technologies, old conflicts: there is a crisis in the field of nuclear disarmament, but hope remains Evgenia Kleshcheva Peace and Security

The multilateral nuclear disarmament system is experiencing a deep crisis, marked by growing mistrust between states. However, positive trends also persist, including the development of nuclear-free zones and the growing interest of young people in the issue of disarmament. Gauhar Mukhatzhanova, a researcher at the UN Institute for Disarmament Research and director of the International Organizations and Non-Proliferation Program at the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, spoke about this in an interview with the UN News Service.

According to Mukhatzhanova, the global arms control architecture, formed over decades, is on the verge of destruction.

“The situation is very difficult now…Progress of multilateral efforts, in particular, has stalled because there is a kind of crisis of confidence in a number of institutions. We are seeing the disintegration of the arms control architecture that was built primarily through negotiations between the Soviet Union – and then Russia – and the United States,” she said.

Threats to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons

After the termination or withdrawal of countries from a number of key agreements, only one remains in force – the agreement between the United States and Russia on the limitation of strategic nuclear weapons. However, START III expires in February 2026, and there are no prospects for developing a new agreement yet.

Gauhar Mukhatzhanova, director of the International Organizations and Non-Proliferation Program at the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, speaks at a Security Council meeting on nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation (archive).

“If nothing follows, we will find ourselves in a situation where nuclear-weapon states will not be able to show progress in implementing Article 6 of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which obliges them to take measures to end the nuclear arms race and strive for nuclear disarmament,” the expert emphasized, noting that this creates a tense background for the next NPT Review Conference. It is scheduled to take place in New York in April and May 2026.

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons is the only binding multilateral commitment to the goal of disarmament on the part of nuclear-weapon states. Opened for signature in 1968, the Treaty entered into force in 1970. On May 11, 1995, the NPT was extended indefinitely. A total of 191 states have acceded to the Treaty, including five nuclear-weapon states. The NPT provides for a review of its operation every five years.

The Return of World Power Rivalry

The expert called the “return of rivalry between world powers” a key factor in the degradation of the arms control system.

“We have returned to a period of serious mistrust between the main actors, and it can be argued that the situation is worse than during the Cold War,” Mukhatzhanova noted.

At the time of the adoption of the NPT, the two leading nuclear powers were the United States and the USSR – realized the need for joint efforts to prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Now, according to her, there is no such understanding, which complicates the work. If key stakeholders are unable to negotiate directly and do not share common positions on key arms control and non-proliferation issues, there is a risk that consensus will not be achieved again at the next Review Conference.

According to Mukhatzhanova, the task before the participating states is to identify those areas on which broad agreement can be found, and try to agree on a document that may not include a large number of details, but will confirm commitment to the fundamental goals of the NPT – preventing the use of nuclear weapons, preventing their proliferation and moving towards disarmament.

Possible nuclear tests – “an extremely alarming signal”

Commenting on statements in the United States about a possible resumption of nuclear tests, the expert noted that the reaction of the international community will depend on the details.

Hiroshima after a nuclear bomb was dropped on the city in August 1945.

If we are talking about hydronuclear (subcritical) tests or flight tests, that is, non-explosive formats, this still creates tension in the context of the NPT and the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). “Previously, the United States itself asserted that hydronuclear tests contradict the CTBT, and now they declare the possibility of carrying them out, since Russia and China are doing it. Does this mean a change in the interpretation of the CTBT? a return to full-scale explosive testing, “we are talking about a radical and extremely negative change that will open the door for other states.”

She recalled that Russia had previously stated its readiness to conduct tests in response to the actions of other countries.

New technologies: accelerating arms races and growing risks errors

Mukhatzhanova noted that technological advances such as hypersonic systems, autonomous platforms and artificial intelligence could significantly change the landscape of strategic stability.

“Hypersonic missiles combine speed and maneuverability… they can better bypass missile defenses and make detection more difficult,” said expert.

Read also:

12,400 nuclear warheads and $2.4 trillion in military spending: why the world needs disarmament

The development of such systems, she said, is pushing other states to increase their own capabilities, forming “a new stage in the nuclear arms race.”

The integration of artificial intelligence algorithms into early warning and decision-making systems is of particular concern.

“The concern is that too much will be left to the discretion of machines… this could lead to unintentional escalation through erroneous interpretation of data,” Mukhatzhanova explained. systems.

Nuclear-free zones: an example of constructive cooperation

Despite the crisis in global architecture, Mukhatzhanova singled out nuclear-free zones as “an example of a positive movement forward.”

“This is an example of how states can jointly imagine their security without nuclear weapons and work to ensure it,” she said. Nuclear-weapon-free zone treaties now cover Latin America and the Caribbean, the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, Africa and Central Asia.

Semipalatinsk test site in Kazakhstan, where the USSR conducted nuclear weapons tests.

In addition to regional nuclear-free zones, there are other international mechanisms and treaties aimed at preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons in certain territories. Thus, the UN General Assembly confirmed the status of Mongolia as a country free of nuclear weapons. The General Assembly is also discussing the creation of a nuclear-free zone in the Middle East region. The sixth session of the Conference on the Establishment of a Middle East Zone Free of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction is being held from 17 to 21 November 2025 at the headquarters of the United Nations. There are also international treaties that limit the deployment of nuclear weapons in special spaces: Antarctic Treaty, Outer Space Treaty and the Moon Agreement, which regulate the activities of states on the Earth, the Moon and other celestial bodies. In addition, the Seabed Treaty prohibits the placement of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction on the ocean floor and in its subsoil.

The expert paid special attention to the Central Asian zone – the youngest and one of the most advanced. This agreement includes commitments to comply with the CTBT, requires additional protocols and emphasizes high standards of nuclear safety.

Mukhatzhanova noted that in this sense, the Central Asian zone can serve as an example for future agreements: the states of the region are able to promote higher standards within the framework of other agreements to which they are parties. According to her, Kazakhstan and now Kyrgyzstan, which have acceded to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), can advocate for stricter verification standards, since the Treaty on the Central Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone itself requires an Additional Protocol along with a comprehensive safeguards agreement. She added that the zone participants also undertake to act in accordance with the CTBT – regardless of whether it has entered into force – and to adhere to nuclear safety standards approved by the IAEA.

Thus, the expert emphasized, this is not only about creating a space free of nuclear weapons, but also about promoting higher standards, which could become an example for other nuclear weapons. agreements.

Grounds for hope

Despite serious challenges, Mukhatzhanova also sees positive trends that allow us to talk about chances for restoring dialogue and reducing risks.

“We were already in a situation of high levels of threat and mistrust – and humanity found a way out through confidence-building measures and arms control,” she said. Based on this experience, the international community is in a better position to work toward restoring or creating a new architecture for arms control and disarmament.

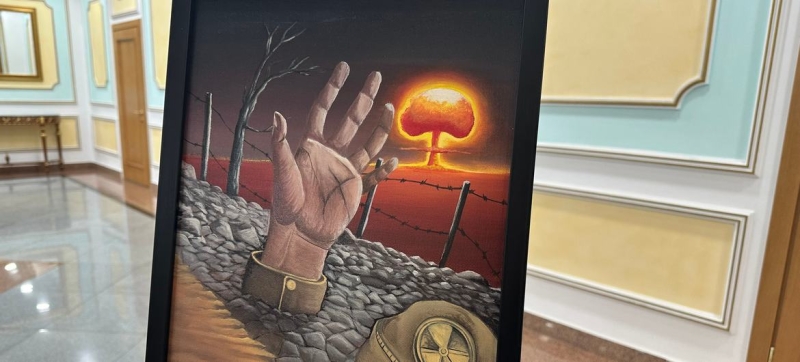

Painting by international anti-nuclear movement activist Karipbek Kuyukov.

Mukhatzhanova also highlighted the growing activism of young people and the willingness of new generations to question the traditional understanding of nuclear deterrence.

“They are ready to question the way nuclear weapons have traditionally been viewed as a guarantor of security. This gives hope,” she said.

The expert also noted the high awareness of the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons and a growing sense of responsibility among states without nuclear arsenals.

“Even the limited use of nuclear weapons will affect countries far beyond the conflict zone… and this understanding can help move forward,” she concluded. expert.